In a recent blog post, Charles E. May describes two kinds of detail that can be found in short fiction:

“One of the most powerful conventions of short fiction is the convention of selection of details. Every story is made up of two kinds of details–those realistically motivated details that exist merely to give the illusion of hard, concrete reality, and those that are mentioned because the teller has a rhetorical purpose for mentioning them….Using the terms of the Russian Formalists, we can think of details in a story merely to give us a sense of actuality as being relatively ‘loose’ and even dispensable, or at least changeable. Details in the story because they are relevant to its meaning or overall rhetorical effect we can think of as being relatively “bound” to the story, that is, intrinsic and not easily detachable or changeable. Trying to determine which details in a story are “loose” and which are “bound” is one of the most important skills for reading stories effectively. One basic way we can determine which details are bound and which are loose is by applying the principle of redundancy or repetition: If a certain detail or kind of detail is mentioned more than once or twice in a story, we might suspect that it is relevant in some way.”

There are those who believe that the factual details of setting don’t matter in a work of fiction. If the “loose” details give the reader some sense of actuality, and if the “bound” details add up to some kind of theme, who cares if they’re factually accurate? This was certainly the attitude of one of the “stars” in a graduate fiction workshop I attended. He was working on a novel set on the edge of a mountain range where I’d spent weeks hiking and doing trail maintenance. The instructor and most of the class thought his novel chapters were effing brilliant – and they might’ve been, in terms of his characters and their twisted emotional lives – but I could barely get through the assigned 45 pages of his work because almost every single detail of setting and natural history he’d included was just dead wrong. He might have driven through the area a couple of times. Maybe stopped at a B&B for the night, or lunched at a local eatery. But that boy NEVER walked up the side of one of those mountains, or if he did, he must’ve had his eyes closed. He knew nothing about the local flora and fauna (you just don’t suddenly find blackberry thickets halfway up the north-facing slope of a mountain in a mixed hardwood forest – blackberries are “edge” plants, and they grow along the boundaries of forest and clearing). He wrote impossible things about the angle of the sun on the mountainside, and what could and couldn’t be seen through the tree cover. Every time I ran across a detail of setting in those 45 pages, it launched me right out of the dream-world that he was working so hard to create. What ticked me off worst when we workshopped was that he simply didn’t care that he’d gotten it wrong. He didn’t care enough about the place he was writing about to get out and learn it.

Not everyone loves natural history. But it’s my personal first choice for nonfiction reading. I can’t travel without picking up guides to the local flora and fauna. It may be a reading tic I developed because I’m from a place where setting is everything – West Virginia. The geography and geology of my home state created its odd shape, its industry and trade, its history, its language – even the character of its people. At the West Virginia Writers’ Conference a few years ago, I attended a session on the importance of setting in fiction. I don’t remember who presented or the main idea of the session, but I came away from it with the conviction that setting is often especially powerful in Southern fiction – and that, for writers from West Virginia, which is a unique place, the importance of setting is inescapable.

So during the first week of July, when I read three stories from New Stories from the South 2010, I did so with a sharp eye on the writers’ use of setting. The first story was Tim Gautreaux’s “Idols,” which refers back to Flannery O’Connor’s stories “Everything that Rises Must Converge” and “Parker’s Back”. I also chose “Ann Pancake’s “Arsonists” and Emily Quinlan’s “The Green Belt” because the writers are from West Virginia and the stories are set there. I read these three stories while spending the first few days of the month back in West Virginia – one day down in coal country (the southwestern counties of the state) – and I particularly wanted to bounce the details of Ann Pancake’s story against the reality of what I saw there. What I found was that the details of setting in “Idols” and in “Arsonists” carry a signficant thematic load. (For reasons of length, I’m going to write about each story in a separate blog post.)

“Idols” continues the stories of two O’Connor characters, Julian (from “Everything That Rises Must Converge”) and Obadiah Parker (“Parker’s Back”). Tim Gautreaux has their lives intersect over the attempted restoration of the old Godhigh mansion, to which O’Connor refers briefly in “Everything That Rises.”

The house takes on new significance in “Idols”: “Normally, he disparaged people who owned large houses, yet deep in his heart he’d stored the memory of the old mansion, the only grand thing in his family’s history. It had shamed him to long for the house, and now he owned it.” In another telling moment, Julian thinks that he had “felt that he deserved this inheritance, had deserved it all his life.” What Julian means by this is one thing; but a close reading of the story reveals a rather different meaning of Julian’s “just deserts.”

When Julian drives up to the house for the first time, he learns that its condition has deteriorated. He sees a five-strand run of barbed wire “healed into the bodies of live oaks.” The lawn is “a weave of waist-high weeds and fallen limbs punctuated by the otherworldly pink domes of thistle blooms, and rising beyond was a mildewed temple. Patches of plaster had fallen away from the main walls, showing orange, wind-washed brick.” The tenants of the old mansion have caused injury to the beautiful old live oaks with their attempt to fence something (cattle?) in; the history of the house, ugly and painful, is growing right into the very trees that surround it. The plaster is a very important image that recurs throughout the story: here, we learn that the Godhighs have plastered over the ugly, utilitarian orange brick from which their house is built – and that the covering lacks permanence.

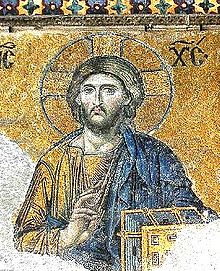

Inside, the house “smells of emptiness and mouse droppings.” There’s a “gassy-smelling stove,” a “badly chipped sink,” and “an attic crossed with naked cypress beams.” The word “crossed” and the use of cypress seem to me to be oblique references to the Crucifixion – a foreshadowing of Obie’s introduction into the story. The metal roof is dented and rusting. (Julian notes that the roof is iron – technically correct, as most metal roofs, though often called “tin roofs,” are made of corrugated galvanized iron, a kind of rolled steel. Later, Obie calls the roof “the tin on top of your importance” – a deliberate disparagement of the house and the importance Julian attaches to it.)

Inside, the house “smells of emptiness and mouse droppings.” There’s a “gassy-smelling stove,” a “badly chipped sink,” and “an attic crossed with naked cypress beams.” The word “crossed” and the use of cypress seem to me to be oblique references to the Crucifixion – a foreshadowing of Obie’s introduction into the story. The metal roof is dented and rusting. (Julian notes that the roof is iron – technically correct, as most metal roofs, though often called “tin roofs,” are made of corrugated galvanized iron, a kind of rolled steel. Later, Obie calls the roof “the tin on top of your importance” – a deliberate disparagement of the house and the importance Julian attaches to it.)

Obie, a down-on-his-luck carpenter, arrives in response to an ad Julian hangs on a bulletin board at the local grocery store. Considering his body as a kind of house and reading its details closely provides significant clues to his role in the story, too (but that would be a different blog post). For my purpose here, it is enough to know that Obie takes the job with Julian to have his tattoos – his “idols,” his estranged wife calls them – removed.

When Obie sets to work, the first repairs he makes are partial and cosmetic: Julian’s priorities are apparently little different from those of his Godhigh forebears. Obie installs a gray breaker box, paints two (but only two!) walls in Julian’s bedroom “an airy, antique white,” and begins to patch an exterior wall with mortar. The breaker box will improve little without replacing the old wiring; the white on Julian’s walls is “antique” – historical – but not pure white, a color symbolically significant in the stories of Flannery O’Connor.

The following week he works on the downstairs bathroom, repairs the sewer line, and installs a cheap air conditioner for his employer’s comfort (while he lives in the vermin-infested kitchen building, built separate from the house to reduce the risk of fire). On one trip to the store, Julian decides not to buy Obie a fan: it is cruel, he thinks, to “make things too comfortable for someone going down in life”—missing, of course, the irony of how far the Godhighs have fallen (and how far he himself is coming down, by spending all his money attempting to repair the irreparable).

Later, discussing the house with Obie, Julian says: “I’ve built up my business, and now I’ve got this big house to keep me busy and give me a place in the world.” At this, a light fixture buzzes; one cannot help feeling that the house itself has just blown a cosmic raspberry at the absurdity of the idea that a house can give one status. “So this here place makes you feel important?” Obie asks. “I am important,” Julian replies. Obie turns to the window, where antique glass (antique again!) distorts everything beyond. He tells Julian that he needs another box of roofing nails to fix the tin on top of his “importance.” Readers, this line just blew me away: I laughed nonstop for five minutes. If I hadn’t loved the character of Obie before, I did ever after.

As repair attempts continue, we learn that Obie “slaves over” corroded wiring and slow-running plumbing – but we are not told that he is actually able to fix it. Eventually, despite low pay and poor conditions, Obie earns enough working for Julian to pay for the removal of his final tattoo, a huge Byzantine mosaic of Jesus on his back. He warns Julian that pride goes before a fall, and says that the doctor was able to take Jesus off him, but not out of him. His idols are gone; he is purified at last. And Obie’s Christianity, unlike the trim of the old house, is internal and permanent rather than external and temporal.

Julian’s treatment of Obie (noblesse oblige at best) and the removal of the final tattoo cause Obie to return to his estranged wife. Julian is left with a mess of a house, a dwindling cash reserve, and no home repair skills: “He could fix a typewriter, but nothing else in the world, and he didn’t know if he could continue living in the old mansion, unable as he was to keep it nailed together.” He realizes that he will be alone in the old house with “a silence as vast as the night.” Readers of Flannery O’Connor know that these are the conditions for revelation. Julian’s chance at epiphany is approaching.

The weather turns cold, and Julian moves out to the old kitchen building, which is more easily heated despite the facts that “its attic [was] full of manic squirrels, its floor a dull smear of ground-in soot and dirt, its walls impregnated with the oily emanations of ten thousand meals.” If the old mansion is a metaphor for Julian’s aspirations, the state of the lowly kitchen house is an even better metaphor for the actual state of Julian’s psyche and his soul.

One night, the temperature drops to nine degrees and even the typewriter oil freezes. This is Julian’s nadir. Obie couldn’t fix anything. Julian can’t even fix a typewriter any more. Who can sort out the mess we make when we try to hold our broken lives and aspirations together – when we try to repair the irreparable? (O’Connor’s answer – and Gautreaux’s, at least in this story – would appear to be Jesus, and Jesus alone.)

Julian determines to try to get Obie back, disregarding the inconvenient fact that he’s out of money and can’t even pay the back taxes (due to 1946) on the old mansion. He goes to the mansion to go to the bathroom, and there discovers disaster. The upstairs toilet (never fixed, remember?) has broken. Water is gushing everywhere. Plaster is falling.

Desperate, he calls Obie, whose hyper-religious wife informs him that he’s so self-indulgent he doesn’t even know what time it is. When Julian insists that he must have Obie, the tart-tongued Mrs. Parker tells him, “People in Hell got to have strawberry shortcake, but they don’t get it.” In an echo of the light fixture, the telephone receiver buzzes another cosmic raspberry at Julian when Mrs. Parker hangs up.

He goes out through the “long, swamped hall” – his personal Slough of Despond – for as John Bunyan says, “still as the sinner is awakened about his lost condition, there ariseth in his soul many fears, and doubts, and discouraging apprehensions, which all of them get together, and settle in this place; and this is the reason of the badness of this ground.” Outside, “the wind flattened the tall dry grass next to the pillars in a dead shout that told him not a thing that would help.” The old mansion has gone from sneering at Julian’s aspirations to refusing him assistance.

Back inside, Obie calls him. The “warm, comforting hand” of his voice does nothing for Julian – though he is able to understand the life-saving message that he should not touch the pump switch to stop the flooding because he will electrocute himself. Julian tells Obie that he needs the carpenter to come back and fix things. Obie uses Julian’s true last name (the common Smith, not the aristocratic ancestral “Godhigh” to which he had pretensions) in his response – “I’m sorry, Mister Smith, but it sounds like things is past fixin’.” He adds that falling plaster (the external) is the least of Julian’s problems, but that if Julian doesn’t know what the problems are, Obie can’t tell him. At this, the light fixture flashes blue sparks – another cosmic comment, using the color that Flannery O’Connor associated with grace and the Virgin Mary. This is Julian’s moment of truth.

Blind, trembling in the wet dark, Julian goes outside to see that the kitchen house is on fire. The fire spreads, burning up his car and killing most of the live-oak foliage. He returns to the house and climbs to the belvedere, where he had initially imagined cotton pickers instead of overgrown fields; now he sees the house as it really is (and perhaps his aspirations as they really are), “naked and singed in a field of white ash.” He hears the voices of “all the families, wealthy and destitute,” who lived there and who abandoned the house either through death or duress.

In this moment, in a final sentence of grace and beauty, Julian is aligned with the great mass of humanity: “Julian felt house and history shrink to nothing beneath him – a void replaced by a vision of himself, dressed in borrowed clothes and defeat, spirited away that very evening on a lurching bus bound for Memphis and sitting next to some untaught, impoverished person, perhaps even another long-suffering and moralizing carpenter.”

I loved the way that Gautreaux allowed the details of the setting – accurate enough to satisfy anyone who has ever tried to restore an old house – to carry much of the story’s thematic load.

I think that Flannery O’Connor would have loved “Idols.” I know I did.