Charles May’s recent blog post (Part One) comparing Margaret Atwood’s “Stone Mattress” and Alice Munro’s “Leaving Maverley” had me trying once again to find something I like about an Alice Munro short story. I enjoyed “Stone Mattress.” I have yet to read a short story by Alice Munro that I’ve found enjoyable. My irritation with her stories seems all out of proportion. And I’ve never been able to put my finger on the precise reason for that irritation. It’s very frustrating to read worshipful paeans to Alice Munro’s stories with the feeling that I just can’t participate in the adulation – that maybe I’m just not quite smart enough to “get” what Munro is up to. May says (apologies if I am not paraphrasing this correctly) that in the details of her stories, Munro compiles patterns of language that, taken together, make thematic and artistic statements.

Could parsing out some patterns in my native language really be that much harder than analyzing patterns of submarine operations? Couldn’t I “get it” just by working hard enough? May left the explication of “Leaving Maverley” to Part Two of his post, and the last time I visited Reading the Short Story, that second part was not yet up. So I thought I’d make a stab at a careful reading of “Leaving Maverley” on my own. I wanted to know if I could find something – anything – to admire.

The reading method I used was the same one that my younger son learned in fourth grade: in a first reading, highlight and note down anything that seems significant. Put it in the left-hand column of a divided page. Put thoughts & comments about the snippets in the right-hand column. Then I took it one step further. I went back and reorganized the snippets, grouping like things together under some general categories, to see if any kind of patterns emerged. Here’s what I found.

Title. “Maverley” sounds about as made-up as a name gets. It sounds an awful lot like “Waverley” – all you have to do is invert the “W.” Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley novels were popular and romantic. Is the story about leaving something popular and romantic – perhaps a form of popular and romantic literature – behind? Uh-oh. Sound the alarm: metafiction alert.

First sentence: “In the old days when there was a movie theatre in every town there was one in this town, too, in Maverley, and it was called the Capital, as such theatres often were.” This sounds almost like the opening to a fairy tale. Nothing I’ve ever read about Alice Munro suggests that she plays with fairy tales. But this sentence seems like a pretty clear marker that we’re about to read something fabulous, perhaps with an embedded moral. Now I’m thinking, “allegorical metafiction.” This causes me an almost physical pain. Perhaps the characters aren’t really characters – they’re personified ideas. Oh, dear. I hope they at least do something a little interesting. There are pages and pages of this story to go.

The first character the reader meets is Morgan Holly, the owner of the Capital theater. He’s a cantankerous fellow who prefers “to sit in his upstairs cubbyhole managing the story on the screen.” Sounds like a typical writer to me: hiding out and managing little story-people. The choice of a theater as the story’s opening setting also suggests that the reader should pay attention to things that are artificial, story-related, popular, and plot-driven. Answering the questions of the new ticket-taker’s father, Holly “doesn’t hire a ticket-taker to gab with the customers” and “did not hire his ticket-takers to give them a free peek at the show.” But he lies about her ability to hear the dialogue while the movie is running. Why dialogue particularly? What’s so special about dialogue? He also says that he doesn’t know what there was to be scared of in a place like Maverley. Indeed. What is there to be scared of in popular, romantic fiction? (Maybe that’s the problem. Maybe good fiction should scare us.) Holly drops out of the story about a third of the way in – poof, finito, gone. He’s no longer necessary to the story, and it’s fine to send him away without much of a farewell. Good-bye, writer.

The next character up is Leah, a young woman from a very religious family who has hired on as Holly’s new ticket-taker. The first (and only) thing she tells Holly – who isn’t particularly interested in his employees as real people anyway – is that her name is out of the Bible. Like Jacob’s unwanted first wife, Leah. In classical literary tradition (e.g., in Canto XXVII of Dante’s Purgatorio), Leah symbolically represents the active (non-monastic) life. She is also fruitful and bears Jacob many children. Because of her father’s religious rules, the Leah of “Leaving Maverley” can’t walk home alone on Saturday nights; the town’s night shift police officer, Ray, is drafted into escorting her home.

After learning that Leah has no idea what the plot of a story is, Ray begins explaining movie concepts to her (more on this below). He tells his wife that Leah has “…something in her…that made her want to absorb whatever you said to her, instead of just being thrilled or mystified by it. Some way in which he thought she had already shut herself off from her family…She was just rock-bottom thoughtful.” He thinks that Leah is moving on, and sure enough, she’s the first character in the story to leave Maverley – to break with tradition. She runs off to marry the United Church minister’s sax-playing son, whom she met while ironing for the minister’s wife (hardly, Ray thinks, much of a foray into the world compared to the theater). This surprises the gossip circuit, because it seems that she only ever met the fellow once (though Isabel remembers that he was flirtatious and forward). In fact, he writes “Surprise Surprise” at the bottom of her letter to his parents. The whole elopement seems like a kind of cliché to me, no real surprise at all; and perhaps it is only the citizens of traditional, romantic Maverley who are truly surprised by the wedding.

Leah pops in and out of Maverley like the mole in a whack-a-mole game. She comes back with his kids, but flirts with Ray at the post office…has an adulterous affair with the new minister himself…and loses the kids to her mother-in-law. She leaves town again and goes to work at the hospital in the city, where Ray encounters her again. The reader might be forgiven for mistaking this for plot. Ray’s comment on the scandal suggests that what lies behind Leah’s comings and goings – her vacillation between tradition and scandalous modern conduct – is more important than whether she wants to start something with Ray, has had an adulterous with the new UC minister, or has done the nasty with an entire regiment of Royal Canadian Mounted Police. He characterizes the scandalous gossip as “…revolting chatter. Adulteries and drunks and scandals – who was right and who was wrong? Who could care? That girl had grown up to preen and bargain like the rest of them. The waste of time, the waste of life, by people all scrambling for excitement and paying no attention to anything that mattered.” Is this what Munro thinks we’re doing if we’re reading traditional fiction? Is that too much of a stretch?

Ray’s character begins in a kind of literary cliché as well. He had joined the Air Force to go to war, because it promised “the most adventure and the quickest death.” (Pretty good description of how I choose my genre-fiction beach reading every summer.) He survives the war when his old crew does not, and he develops survivor’s guilt – “a vague idea that he had to do something meaningful with the life that had so inexplicably been left to him, but he didn’t know what.” This seems like another traditional convention – something that has been said and done before, and that smacks of plot, especially because he doesn’t seem to do anything meaningful with the life – at least the part of his life that the reader sees.

Ray enrolls in school after the war and falls in love with Isabel, his married English teacher; she breaks tradition, divorces her bemused husband, and marries Ray. Like Leah’s sister and nemesis Rachel, Isabel is barren. And she and Ray can talk about everything – except whether or not they are disappointed that she can’t have children.

Other than that, Isabel and Ray can talk “anytime about anything” – at least, until Leah disappears. Isabel’s reading tastes are described in some detail. She forms a women’s group to read Great Books: “A few had not understood what this would really be like and dropped out, but aside from them it was a startling success. Isabel laughed about the fuss there would be in Heaven as they tackled poor old Dante.” She also reads magazines – described by Munro in a way that is clearly a big sloppy wet kiss for The New Yorker, which has published many of her stories: “…serious and thought-provoking but with witty cartoons that she laughed at.” Isabel laughs at cartoons, news of the town, magazine ads for furs and jewels. Isabel has a heart condition that forces her to quit teaching: “She could never teach again. Any infection would be dangerous, and where is infection more rampant than in a schoolroom?” In traditional literature, Rachel symbolizes the contemplative or monastic life (which might include academia these days); but the comment about schoolroom infections certainly sounds to me like a poke in the eye of academia. Hmm.

One important function that Isabel seems to have is that of providing a kind of lit-crit commentary on the story of Leah. When Leah runs off with the minister’s son, Isabel finds that to be “a great story.” Later, upon being told of the scandalous affair between Leah and the new minister, she says that Leah’s story “sounds pretty commonplace, after all.”

Isabel and Ray’s conversations are brought to a temporary halt first by Leah’s disappearance, and then more permanently by Isabel’s illness. In the first instance, the fault is Ray’s: his conversation circles back to his visit with the (first) United Church minister. Isabel’s only response is a cynical comment on the futility of prayer.

In the second instance, Isabel has also left Maverley. She is in the hospital in the city, and has become too ill to enjoy her former pastimes. He tries to distract her “with lively talk of the past, or observations about the hospital and other patients he got glimpses of. He took walks almost every day, in spite of the weather, and he told her all about those as well. He brought a newspaper with him and read her the news.” He hopes that these stories will somehow revive her. She says that it’s good of him, but she seems to be “past it.”

Two final things – themes? – that I noticed in patterns in the story are religion and the craft of stories.

There are three religious perspectives mentioned in the story. There is the traditional fundamentalism of Leah’s father, who seems to believe that stories like the ones shown in the theater will corrupt his daughter and whose religion seems to be based on rules. (The second time Ray meets Leah, he thinks that her traditional religious upbringing hasn’t completely been eradicated from her psyche.) By contrast, Isabel is an atheist: she jokes that her pericarditis is God’s punishment for her amorous adventure, which is a waste of time since she doesn’t believe in God anyway. Finally there are the two United Church ministers – the “old” one, whom Isabel characterizes as “a very up to date minister who went in more for the symbolic,” and his replacement, who doesn’t wear his clerical collar and who seems uncomfortable ministering in public. When caught out with Leah, he makes a public declaration:

“Everything had been a sham, he said. His mouthing of the Gospels and the commandments he didn’t fully believe in, and most of all his preachings about love and sex, his conventional, timid, and evasive recommendations: a sham. He was now a man set free, free to tell them what a relief it was to celebrate the life of the body along with the life of the spirit.”

This UC minister, Carl, never marries Leah. He eventually marries another (female) minister, and now serves as minister’s wife.

I could be dead wrong here, but I don’t think these contrasts have much to do with actual religious beliefs. I think they’re a stand-in for various critical positions on literature. This is where I regret not taking a graduate level class in literary theory. (No, really, I don’t regret that. But.) I don’t know enough about lit crit to understand fully what Munro means. If she were one of my Russians, the story would come with a lengthy footnote excerpting the author’s letters to her contemporaries, in which she took grand positions on matters of critical philosophy. I could use that kind of help here!

Finally, in “Leaving Maverley” Munro stacks up what I read as a kind of indictment of artifice in literary craft. First, Ray has to tell Leah what a plot is – that it means that a story is being told. He prefaces his explanation by telling her that “he didn’t get too involved in the movies, seeing them as he did, in bits and pieces. He seldom followed the plots.”

Then there’s a wonderful passage in which Ray is explaining movies to Leah:

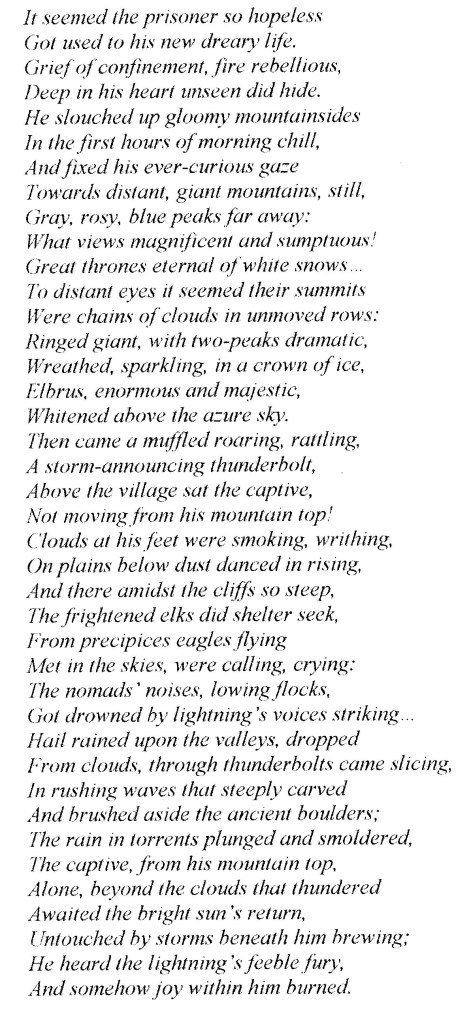

“He was called upon not to tell any specific story – which he could hardly have done anyway – but to explain that the stories were often about crooks and innocent people [the antagonists and protagonists!] and that the crooks generally managed well enough at first by committing their crimes and hoodwinking [action!] people singing in night clubs (which were like dance halls) or sometimes, God knows why, singing on mountaintops or in some other unlikely outdoor scenery, holding up the action [setting and pacing!]. Sometimes the movies were in color [sensory detail!]. With magnificent costumes if the story was set in the past. Dressed-up actors making a big show of killing one another. Glycerin tears running down ladies’ cheeks. Jungle animals brought in from zoos, probably, and teased to act ferocious [artifice! Verisimilitude!]. People getting up from being murdered in various ways the moment the camera was off them. Alive and well, though you had just seen them shot or on the executioner’s block with their heads rolling in a basket.” [This, perhaps, is the ultimate crime of popular fiction: it lies about the reality and finality of death.]

There are a few more jabs at literary craft. On point of view & language: “She could almost have been one of Isabel’s new friends, who were mostly either younger or recently arrived in this town, though there were a few older, once more cautious residents, who had been swept up in this bright new era, their former viewpoints dismissed and their language altered, straining to be crisp and crude.” On voice: “Leah greeted him with a new voice and pretended to be amazed that he had recognized her, since she had grown – as she put it – into practically an old lady.” The new voice is a seductive one, and she uses it to talk to the new UC minister, with whom she eventually has an affair. Finally, on naming: Ray notes that the names of Leah’s children, David and Shelley, are “fashionable.”

The final section of “Leaving Waverley” takes place after Isabel dies (while Ray is fending off a last scandalous hit from Leah in the hospital basement fitness room). This section struck me as being noticeably different from the rest of the piece in some way that I can’t quite put my finger on. Ray ties up some logistical details after Isabel’s death, much as Munro is tying up the end of the story; “Leaving Maverley” ends on an odd note of loss. Ray has lost Isabel, of course, but that’s just a kind of plot point. He thinks about Leah’s loss of her children, and how she is an expert at losing compared to him. One of the things he has lost is Leah’s name; when he remembers it, his relief is “out of all proportion.” That phrase seems too significant to mean “out of all proportion for what Ray felt about Leah;” it seemed to be about something else altogether. Perhaps he has lost some connection to or memory of the active life because he has left Maverley?

At that point, I was lost too. I can’t for the life of me see how the idea of what is lost and what remains ties back to any of the other thematic ideas I thought had been developing over the course of the story. That makes me wonder if I was barking up the wrong tree all along.

Taking a leap of faith, I’m going to ask: what is lost and what remains when we “leave Maverley” – when literature (its writers? its critics?) depart from traditional, romantic, plot-driven stories? From the artifice that is at the heart of fiction? I don’t have an answer to that, unless it’s that one gets an Alice Munro story that must be absorbed, because it neither thrills nor mystifies in a traditional way.

For whatever reason, I thought I was hearing Munro’s voice the loudest in the character of Isabel. I picture her answering my question about “Leaving Maverley” in the same way that Ray imagines Isabel responding to the “revolting chatter” about Leah’s affair: “Not that Isabel would have been looking for answers – rather, that she would have made him feel as if there were more to the subject than he had taken account of. Then she’d have ended up laughing.”

And that, my friends, is the bottom line on why I don’t enjoy Alice Munro’s stories. She makes me feel as if there’s more to the story than I’ve taken account of. Then she ends up laughing.